The elders of the gymnasium

The polis was fuelled by money. Honours for the gods, political institutions, and public buildings all had to be paid for. Yet this did not only happen through a city’s authoritative bodies, like the council and assembly. Over the last year, as I have surveyed the epigraphic evidence of pre-Roman Anatolia as part of the CHANGE project with a view to establishing categories of monetary activity, it has been important to look deeper. In particular, we might consider the role of associations in the life of the monetary economy – groups beyond civic bodies with their own administrative structures and corporate identities. In the Hellenistic period, one obvious place is the gymnasium – an institution that virtually became synonymous with the identity of being a polis, and is attested from mainland Greece to Bactria, and the Black Sea to Egypt, from the late 4th to 1st centuries BCE. Here, male citizens of the future underwent rigorous physical and intellectual training, honed bodily prowess and combat skills, attended lectures by literati, and imbibed local tradition and history through participation in parades and festivals. Gymnasia, however, were not always official ‘civic’ institutions, and had their origins as private associations. In the Hellenistic period, this associative character continued, with the gymnasium’s main sub-groups of the ephebes (those aged between 18 and 20 years) and neoi (those between 20 and 30) acting as independent bodies. One particular sub-group, however, is more obscure: the presbyteroi, or ‘elders’, comprising those of post-neoi status aged over thirty. These have been studied most recently by Pierre Fröhlich and Klaus Zimmermann, and are known exclusively from epigraphy. What evidence we have informs us about the role of gymnasia as intermediaries between civic identity and monetary economy.

Presbyteroi are mentioned in several documents scattered across western Asia Minor (Pergamon, Kolophon, Metropolis, Ephesos, Miletos, Magnesia, Iasos, Euromos), its offshore islands (Mytilene, Chios, Samos, Kos, Rhodes, Amorgos), northern Greece (Amphipolis), and also north Africa (Cyrene). These documents comprise honorific decrees and inscriptions on statue-bases, as well as lists of ephebes and dedications of gymnasiarchs, and date almost entirely to the 2nd century BCE and later, with presbyteroi attested also in the 1st century CE. Most of the attestations reveal little more than the sheer fact of the corporate existence of the ‘elders’. They do show, however, that they were organised in ways not dissimilar to other groups in the gymnasium. For instance, a decree from Kolophon records that banquets were donated by unnamed kings that were to be attended by the neoi and presbyteroi, showing that they shared in the activities of younger members of the gymnasium (SEG 39.1244ii ll. 47-48). We also know of gymnasiarchs specifically appointed to take charge of the presbyteroi from Rhodes, Magnesia and Cyrene, and honorific monuments set up by the presbyteroi, similar to those erected by the ephebes and neoi for their benefactors. Briefly put, the presbyteroi comprised an older age group of over-thirties who continued the gymnasial training and associative life of their younger years.

Several documents from Iasos show slightly more. One is a mid-2nd-century honorific decree of the presbyteroi for a Kritios son of Hermophantos (I.Iasos 93), inscribed on a column probably belonging originally to the gymnasium known as the Antiocheion (presumably because it was sponsored by either Antichos I or III). His initial service had involved inscribing the archives of the presbyteroi with the help of a public slave, while at a later stage he was ‘elected dioketes by the presbyteroi, and, not wishing to speak against them, he handed over the accounts and monies with his fellow dioketai to the dioketai who would succeed them in a respectful and just manner’. It would seem, then, that as well as being a group within the gymnasium the presbyteroi administered their own affairs, handled their own documentation, elected their officials at their own assembly, and managed their own funds. The end of the decree even preserves the number of voters who decided on Kritios’ honours – seventy in favour, four against. What precisely they spent money on we can only guess at, but we might suppose this included the supply of oil, and perhaps items for contests, such as equipment and prizes. Another inscription (dating perhaps to the 1st century BCE) recording the endowment of a certain Phainippos (I.Iasos 245) offers further detail. This also mentions the dioketai of the presbyteroi, and intriguingly specifies that they were to provide 150 drachmas from the income generated by the endowment, which would go towards making offerings at Phainippos’ tomb. It is likely this sort of private benefaction formed the main source of the wealth of the presbyteroi.

More interesting still is another Iasian decree, this time recording the resolution of the city’s council and assembly (I.Iasos 23), also inscribed on a column. We are probably here in the early 2nd century. The presbyteroi were to be allowed ‘to recover the monies that they held in common from those who had borrowed from it, and had not returned it in due time, just as was permitted to the neoi’. We see here that the presbyteroi behaved just like the city, in growing its capital by lending to private individuals – this is also the procedure implied by the endowment of Phainippos, which would presumably have been lent out to generate the 150 drachmas for his posthumous rites. A parallel for this practice is another decree from Patmos, of the 1st century BCE, where a gymnasiarch Hegemandros donated 200 drachmas to ‘the lampadistai and those sharing in the anointment’ – an association probably very similar to the presbyteroi, but on one of Miletos’ offshore islands – with the express purpose that ‘it would be lent out at interest’.

Back at Iasos, it would also seem that these particular funds in some way intersected with those of the city; it may also imply that the presbyteroi may have received some income from the city, as part of the ‘monies held in common’. The decree further mentions, however, that the denunciations of the presbyteroi before the civic assembly were made in accordance with the proposal of a certain Thalieuktos (τὸ Θαλιεύκτου διόρθωμα), which had regulated the treatment of debtors in arrears. Iasos had borne the brunt of the war between Antiochos III and Rome in the 190s BCE, and had been riddled with political division as a result: it is conceivable that these measures against debtors were aimed at resolving tensions between opposing parties, and resolving a shortage of public money caused by the war. In any case, the intervention of the city in the presbyteroi’s finances, and the implication that the latter received funding from the city, may in this case have been exceptional, and not the norm.

The picture these decrees reveal, of presbyteroi managing their own finances and operating as an association, fits the pattern we find with other non-civic associations in the Hellenistic world. Their further interest lies in the fact that they seem to have behaved as a distinct association within the gymnasium, itself already somewhat distinct from civic authority – as mentioned in the decree on the debtors, the neoi also managed and lent out their own money. Why the presbyteroi, at least at Iasos, should have felt the need to differentiate themselves from other gymnasial groups in an administrative sense is unclear, although their chronological specificity is potentially relevant. While the other three groups (boys, ephebes, neoi) are already attested in the late 4th and 3rd centuries BCE, references to the presbyteroi do not antedate the early 2nd century, the earliest document being the Iasian decree on debtors. This is not to say that groups of gymnasial elders did not exist before this time, of course. In fact, references to the aleiphomenoi, ‘those who are anointed’, distinguished from the neoi and implying a status like the over-thirties, can already be found in the late 3rd century. The generalisation of gymnasia across the eastern Mediterranean, and increased participation by citizens in gymnasial training, seems nonetheless to have gradually led to the crystallisation of the post-neoi as the presbyteroi, reflecting acceptance of a group on the basis of their age-category, and not merely on the sheer basis of their identity as the ‘anointed’. This process was not uniform and omnipresent, and some cities still continued to call their non-ephebe, non-neoi members the aleiphomenoi, and not presbyteroi. Once conceived, however, the latter term set a new standard, and it is certainly the case that from the 2nd century BCE onwards the presbyteroi become more epigraphically visible, and this should be understood to reflect both their coherence as a group, and a yearning for social distinction.

Attestations of the presbyteroi are also heavily concentrated in western Asia Minor and its offshore islands, and we might therefore reasonably wonder if the political and economic conditions of this region, especially in the aftermath of the retreat of Seleukid dominance after the peace of Apameia in 188 BCE, abetted the emergence of presbyteroi. The later Attalid dynasty, the main royal power in the region from this point onwards, is well-known to have promoted the gymnasium as a place for communication between kings and the civic elite. Moreover, civic communities outside the Attalid realm in Karia and later Lykia (after 167), free from the overlordship of kings and imperial rulers for perhaps the first time in half a millennium, grew confident and competitive, even engaging in local wars. In this context civic authorities invested more heavily in their gymnasia than before, as sites of civic identity and military training: some of the largest gymnasia ever built in the Hellenistic period, at Pergamon and Stratonikeia, were completed after 188.

Wealth levels among citizenries also rose. The 2nd century, as is well-acknowledged, is also the period when powerful civic leaders exerted influence over their communities as benefactors in new and striking ways, like the remarkable woman Archippe, who built Kyme’s bouleuterion in the late 2nd century. The twin forces of rising pride in gymnasia, and increasing wealth-levels, can be seen as the motors powering the emergence of presbyteroi – the wealthy elite who had engaged in training as ephebes and neoi, and sought to perpetuate the social distinction associated with gymnasia into their thirties, their ‘elder’ years. The level of financial organisation we have observed at Iasos, if indeed reflective of wider practice, reflects the peripherality of the presbyteroi to civic authority: unlike the ‘core’ earlier age-groups of the ephebes and neoi, cities may not have felt as strong a need to continue financing gymnasial training for those of post-neoi status. It is possible that the activities of the presbyteroi were mainly ‘voluntary’, while also extending beyond what the neoi and ephebes did. The endowment of Phainippos, mentioned earlier, was concerned primarily with organising sacrifices and a banquet, and rites at his tomb, and seems to have been made out only to the presbyteroi. Another fragmentary inscription records the endowment of another Hierokles (I.Iasos 246) in very similar wording, suggesting this was one of the association’s ‘standard’ practices. While ephebes and neoi commemorated great civic benefactors at public funerals, as is attested elsewhere, it may be that presbyteroi had the additional function of commemorating fellow members of the gymnasium itself, acting as something like a burial society.

What little we can glean of the otherwise obscure presbyteroi, then, seems to demonstrate the role of the gymnasium, in particular in its later Hellenistic phase, as an institution not only crucial as a source of cultural and ideological capital, but also as one of the spaces where financial complexity could emerge, and associative groupings beyond the city could thrive, precisely because of its cultural and ideological importance. Money funded civic pride through the gymnasium, and over time this created spaces for the alumni of the neoi, the presbyteroi, to strive for social distinction, and act as creditors. In time to come it is such groups of elderly fanatics of the gymnasium that may have laid the basis for the gerousia, the assembly of seniors widely attested in cities of the imperial period.

The blog of the CHANGE project, based at the CSAD in the Faculty of Classics, University of Oxford, between 2020-2025. We will be adding regular updates on our research and news of our project publications.

CHANGE: The development of the monetary economy of Ancient Anatolia c 630-30 BC has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 865680).

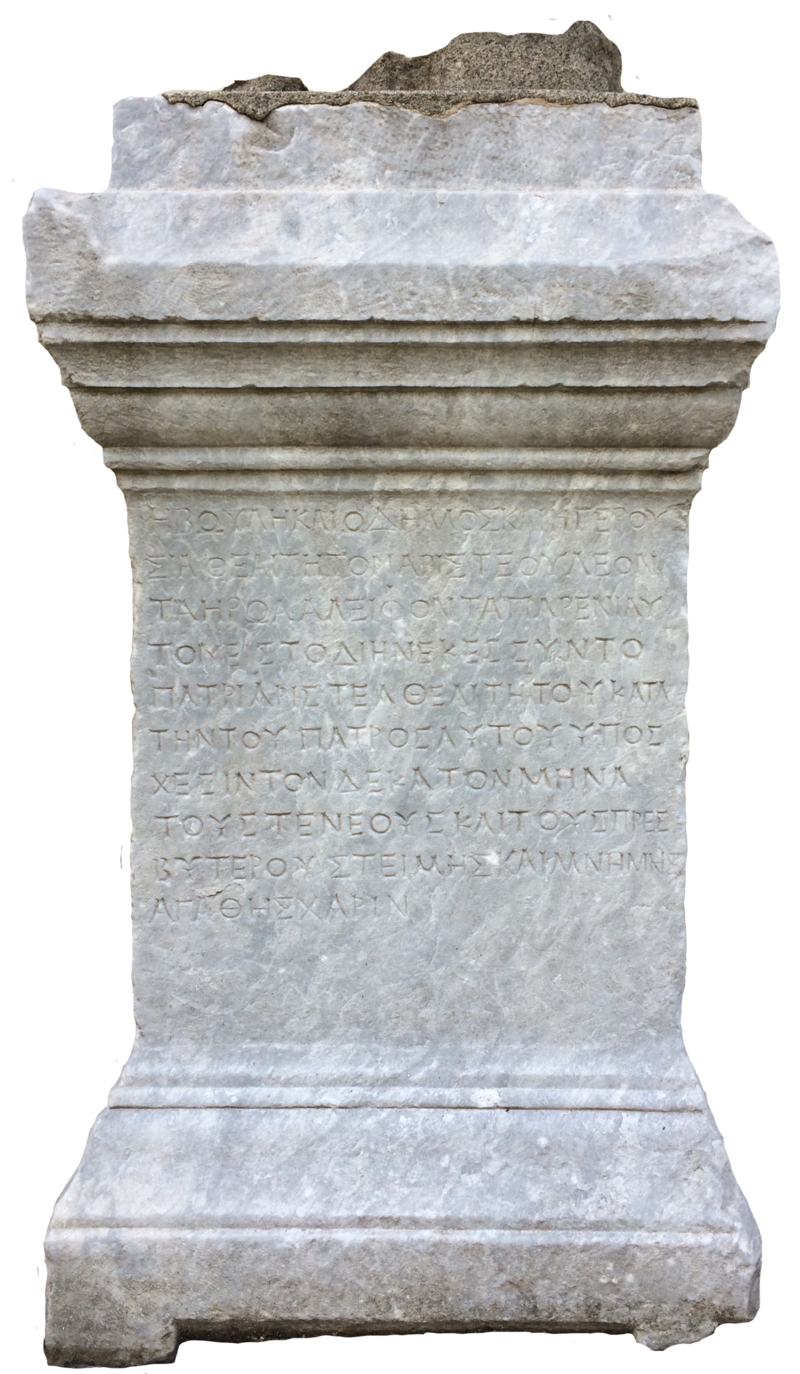

Honorifif statue base for THeaitetos Leon, who distributed oil to the neoi and presbyteroi, lat 1st century CE. Istanbul archaeological museum, photo Marcus Chin